Same CVE, Different Risk: Why Runtime Context Changes Everything

A deep dive into how runtime evidence transforms vulnerability prioritization.

Published on

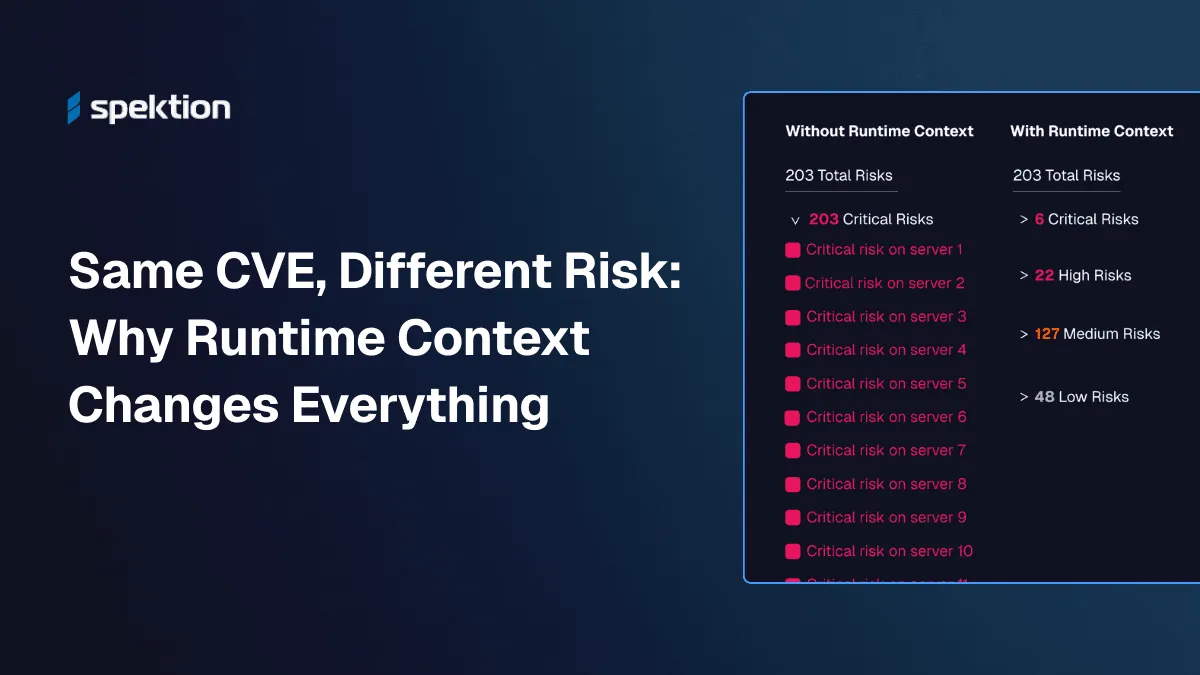

Suppose you run a vulnerability scan and it comes back with 203 critical vulnerabilities. Next, you add runtime context. Those same 203 issues turn into something more useful: now you have 6 emergencies, 22 high-priority items, and 175 findings for your normal patch cycle.

The difference has a significant impact on operations. Emergency remediation has costs: both in direct resources and opportunity costs. Every engineer who gets pulled into an emergency patch cycle stops shipping new features, improving stability, or paying down technical debt. Shifting out of emergency mode and into scheduled patch cycles protects engineering capacity for planned work. Even in the most collaborative IT-security relationships, emergencies can be a political capital drain on the security program, and the price of a perceived false alarm is credibility.

Consider the well-known CVE-2024-53677, a critical remote code execution vulnerability in Apache Struts with a CVSS score of 9.8. Struts powers countless enterprise Java applications: customer portals, internal tools, and payment systems. When this CVE dropped, scanners flagged all your 203 servers running a Struts-based application as critical. In reality, not all of them were.

The question is: how do you tell which ones are truly critical, so you can prioritize not just patching, but other mitigations until patches can be applied?

Three Approaches to Vulnerability Prioritization

Not all “contextual” prioritization is created equal. There’s a spectrum:

Level 1: Scanner-defined severity. CVSS scores straight from the NVD. Every instance of CVE-2024-53677 gets a 9.8, regardless of your environment. Oftentimes, these are elevated with a vendor-specific risk score, taking EPSS and/or exploit intelligence into account. This is a simple approach, but it won’t help you prioritize. You end up treating a dormant staging server the same way you treat your payment processing system.

Level 2: Model-based inference. This is where most “contextual” vulnerability management tools live. They integrate with your asset inventory, threat intel feeds, and network topology. They build models. They claim to know what’s exploitable in your environment.

But look at what they actually see: CVE metadata, global exploitation patterns, asset lists, and network diagrams. Their data is as accurate as what is populated in your own IT inventory systems. From this, they infer whether software runs, what privileges matter, and what the blast radius would be.

Inference is not observation. Level 2 asks: “Is the process running?” Level 3 asks: “What is the process doing?”

Level 3: Runtime evidence. Actual telemetry from your environment showing what’s executing, with what privileges, accepting connections from where, and with access to what resources. Combined with threat intelligence on active exploitation, this is the only approach that tells you what’s actually at risk, not what might be. Furthermore, it’s evidence-based, so your defense and the credibility of the vulnerability management team isn’t being bet on theoretical models.

The Inference Problem

Every modern vulnerability management tool promises “context.” However, most are still guessing, just more sophisticatedly than CVSS alone.

Here’s what inference-based VM tools assume versus what might actually be true:

| What VM tools infer | What might actually be true |

|---|---|

| Installed software is running | May be installed but never executed |

| Running software uses its granted privileges | May run with restricted privileges in practice |

| All code paths are equally risky | Only specific code paths execute in your deployment |

| Network-exposed means exploitable | The software is actively listening to accept connections |

| Blast radius follows network topology | Actual lateral movement depends on the credentials accessed |

How confident are you that your tool’s inferences match your reality?

What Runtime Evidence Actually Shows

Let’s walk through the four factors that differentiate risk for CVE-2024-53677 across your 203 Struts servers. For each factor, I’ll contrast what models infer versus what runtime observes.

Factor 1: Execution State

What models infer: The software is installed (or, more precisely, the CMDB says it’s installed); therefore, it’s a risk.

What runtime observes: Whether the software is actually executing. Not what the CMDB claims. Not what was installed last quarter. What’s running right now, with real-time notification when execution state changes.

When I ran security programs, I dealt with multiple incidents where the compromised asset “didn’t exist” according to configuration management. It was missed in a change ticket, believed to be decommissioned, or never captured in the first place. Any tool that models risk from CMDB data inherits all of CMDB’s blind spots. Whereas, runtime observation doesn’t care what the CMDB says.

In enterprise environments, installation doesn’t equal execution. Legacy software lingers from previous deployments. Applications get installed for testing and are never removed. Packages come bundled with other software, but are never used.

Vulnerabilities in software that hasn’t executed in 90 days warrant a different urgency than vulnerabilities in code running continuously in production. Both need remediation, but not on the same timeline. The key is continuous observation: when a dormant process starts executing, your vulnerability prioritization should update immediately, not at your next scan cycle.

Factor 2: Privilege Level

What models infer: The service account has SYSTEM privileges, therefore exploitation may grant SYSTEM access.

What runtime observes: What privileges the process actually exercises. A service might have elevated permissions but run with restricted tokens in practice.

With SYSTEM or root privileges, attackers can access credentials stored in memory, install persistence mechanisms, disable security controls, and move laterally across your environment. With limited privileges, they need additional exploits to escalate. Each step is a chance for detection.

CVSS captures privileges required before exploitation. Runtime analysis tells you what the attacker gains after exploitation, a much more relevant factor for prioritization and implementing layered defenses to combat exploitation.

Factor 3: Network Exposure

What models infer: The server appears in network diagrams as internet-facing; therefore, the service is exploitable remotely.

What runtime observes: Whether the vulnerable service is actually accepting connections. Is it bound to localhost or listening for external connections?

A Struts application that only accepts connections from your internal load balancer is fundamentally different than one exposed directly to the internet. Although the CVE is identical, the actual risk is not.

Traditional scanners can’t see this. They know the software is vulnerable. They don’t know whether the vulnerable code path is actually reachable.

Factor 4: Blast Radius

What models infer: Blast radius follows network topology and asset criticality tags.

What runtime observes: What credentials the process has actually accessed, what systems it has actually connected to, what data it has actually touched. Demonstrated behavior, not theoretical access.

A compromised Struts application serving your marketing website is serious. A compromised Struts application processing payment transactions, with observed access to database credentials and demonstrated connections to downstream financial systems? That is catastrophic.

Runtime evidence shows you demonstrated behavior: what software has actually done. This provides a stronger signal for vulnerability prioritization than theoretical access models. Adversaries may explore paths the software hasn’t historically used, but “has accessed sensitive credentials” is a more concrete risk indicator than “might be able to access sensitive credentials.”

How These Factors Combine

Runtime vulnerability prioritization isn’t a checklist. Rather, it is a framework to guide decisions. If there’s active exploitation happening in the wild, that elevates priority regardless of other factors. But without active exploitation, the factors interact and work together:

- Not executed in 90+ days, no active exploitation → Scheduled patch cycle

- Executing regularly, limited privileges, internal-only → Medium priority

- Executing regularly, elevated privileges, internet-facing → High priority

- Executing regularly, elevated privileges, internet-facing, demonstrated access to sensitive credentials, active exploitation → Emergency

The point isn’t to create another scoring algorithm. It’s to give your team evidence for each factor so that prioritization decisions are defensible.

Putting It Together: Evidence-Based Vulnerability Prioritization

Your scanner flags CVE-2024-53677 on 203 servers running applications built on Apache Struts. All rated CVSS 9.8 Critical. A model-based tool might adjust scores based on asset criticality tags and network zones, but it’s still inferring.

Here’s what runtime evidence reveals:

48 servers have the application installed but not executed in over 90 days (staging environments, dormant deployments). Still patch them, but in your normal maintenance cycle, not as emergencies.

85 servers are executing regularly, but only accept connections from internal networks, behind multiple firewall layers. Medium priority for your normal patch cycle.

42 servers are running internet-facing applications, but as limited service accounts with no observed access to database credentials or sensitive data. Medium-high priority.

22 servers are internet-facing, running as root, with demonstrated database connections. High priority.

6 servers are internet-facing, running as root, with observed access to payment processing credentials and demonstrated connections to downstream financial systems. Those are your emergencies.

Same CVE. Same CVSS score. Five completely different risk profiles based on observed evidence, not inferred probability.

The Questions to Ask

Before trusting any vulnerability prioritization approach, ask:

- Does it show which processes are actually executing, or infer from installation data?

- Does it notify you in real-time when execution state changes, or rely on periodic scans?

- Does it show privileges exercised, or just privileges granted?

- Does it show observed credential access, or theoretical access based on permissions?

- Does it show what’s actually running, or what your CMDB says should be running?

- Does it show observed network exposure, or inferred exposure from topology diagrams?

- Does it show evidence of behavior or probabilities?

If the answers are inference-based, you’re still guessing, just more sophisticatedly than CVSS alone.

Why Runtime Context Matters in Vulnerability Management

Runtime context doesn’t just change your patch list. It changes the conversation with engineering.

When you tell a development team, “This CVSS 9.8 is critical,” they’ve heard that before. But when you tell them, “This specific instance is running as root, internet-facing, with observed access to your payment database credentials, and threat intel shows active exploitation in the wild,” you’re giving them evidence they can act on.

Your remediation teams are tired of probability scores they can’t defend to skeptical stakeholders. Give them evidence instead.

You’re no longer the team that cries wolf on every critical CVE. You’re the team that can explain exactly why 6 of 203 findings need emergency action, and the rest can wait.

###

Stay tuned for the next article in this series: The Vulnerabilities Your Scanner Will Never Find, on detecting exploitable conditions that exist before a CVE is published, and the risks in custom code that no scanner database will ever cover.