Your Scanner Found 50,000 Vulnerabilities. Most Don't Matter.

Why traditional vulnerability management creates the illusion of security while leaving teams drowning in noise, and why runtime context is the way out.

Published on

Your team can’t patch all your organization’s vulnerabilities. Nobody can. And the way most organizations prioritize which vulnerabilities to fix first is fundamentally broken.

In 2024, 40,077 new CVEs were published, a 38% increase from the year before and the seventh consecutive year of record highs.[1] If you’re running a mid-market security program, your vulnerability scanner probably surfaces tens of thousands of findings, with a healthy percentage marked “Critical” or “High.”

Here’s what the data actually shows: Datadog’s 2025 State of DevSecOps report found that after applying runtime context (factors like whether the vulnerability is actually running in production, or if the application is exposed to the internet), only 18% of vulnerabilities rated “Critical” by CVSS remained critical.[2] The problem isn’t the volume of vulnerabilities. It’s that we’re measuring the wrong things.

The CVSS Trap

Most vuln management programs rely on CVSS scores as their primary vulnerability prioritization mechanism. A peer-reviewed study in ACM’s Digital Threats: Research and Practice examined the correlation between CVSS scores and real-world exploitation and found no linear relationship. The researcher concluded that “a resource-constrained IT organization…would be better off patching any random 100 CVEs with a CVSS score of 7 than they would by doing the same for a group of CVSS 10s.”[3]

The math is brutal. According to Tenable’s research, 56% of all vulnerabilities are scored as High or Critical by CVSS.[4] When everything is critical, nothing is.

Why the disconnect? Because CVSS measures theoretical severity in a vacuum. It answers “how bad could this be?” not “how bad is this for us?” A critical vulnerability in software that isn’t running poses zero risk. A high-severity flaw requiring local access on a machine with no network exposure isn’t remotely exploitable. CVSS can’t tell you any of this. It was never designed to.

The Threat Intelligence Layer

Risk-Based Vulnerability Management emerged to solve this problem. Kenna Security played a pivotal role in advancing the category, producing research that proved CVSS correlated poorly with actual exploitation. That work helped spawn EPSS (Exploit Prediction Scoring System) and influenced how many vulnerability management vendors approach prioritization today.

These tools help. Layering threat intelligence, exploit availability data, and machine learning on top of raw findings helps teams cut through noise. Many vulnerability management tools and vendors now incorporate these signals. But reducing 50,000 CVEs to 5,000 based on global threat projections still leaves you with 5,000 CVEs, and no way to know which actually matter in your environment.

VulnCheck’s 2025 research revealed that EPSS functions largely as a trailing indicator. Their Q1 analysis found that few KEVs had elevated EPSS scores on the same day exploitation evidence became public, despite active in-the-wild exploitation.[5] The problem isn’t that threat intelligence tools are wrong. It’s that they optimize for a question one step removed from what security teams need to answer. They tell you what’s dangerous globally. They can’t tell you what’s dangerous here.

The Missing Layer: Your Environment

Consider two identical servers running the same software with the same CVE. Server A runs the vulnerable application as a privileged service, exposed to the internet, with credentials for lateral movement cached in memory. Server B has the software installed but not running. It was part of an old deployment that was never fully cleaned up.

Your vulnerability scanner sees the same CVE on both machines. CVSS gives them the same score. Threat intelligence says the same exploits exist. But the actual risk? One is critical (Server A). One is negligible (Server B).

No amount of theoretical modeling or global exploitation data can distinguish between these two scenarios. Only evidence from the environment itself (runtime behavior, network exposure, privilege context) can close that gap.

Research from Rezilion and the Ponemon Institute examined this directly. Their analysis found that organizations face massive vulnerability backlogs: 66% reported backlogs exceeding 100,000 vulnerabilities, with an average of 1.1 million per organization. Yet 53% of security leaders believe it’s important to focus only on those vulnerabilities that pose the most risk, rather than attempting to remediate everything.[6]

The Credibility Problem

The deeper cost isn’t technical. It’s organizational.

Vulnerability management sits at the intersection of security and engineering, and that intersection runs on credibility. Every patch request is a negotiation. Every maintenance window is a trade-off against feature work, system stability, and the other dozen priorities engineering teams are juggling.

When you force a maintenance window for a vulnerability that wasn’t actually exploitable in that environment, you’ve created disruption without reducing real cyber risk. Engineering teams figure this out. They start asking, “Was that really necessary?” And when they stop trusting your severity assessments, getting buy-in for the next emergency patch becomes a fight.

Joe Silva, Spektion’s CEO and a former Fortune 200 CISO, lived this dynamic for eight years:

“Vulnerability management was the biggest political capital drain I dealt with. You’re constantly negotiating with app owners and infra teams, fighting for improved maintenance cadence, and burning credibility on patches that may or may not matter, because you can’t actually prove which ones do.”

The teams that own the systems aren’t ignoring security. They’re making rational decisions based on the information they have. When that information is “CVSS says it’s a 9.8,” they’ve learned that doesn’t mean much. The problem isn’t their skepticism. It’s that the data we’re giving them doesn’t justify the disruption we’re asking for.

What Would Change Everything

What if you knew, for each vulnerability in your environment: Is the software actually running, or just installed? What privilege level does the vulnerable process have? Is the service reachable over the network, or only locally accessible? If an attacker exploited this, what could they actually do next?

This is runtime context: the data your vulnerability scanner can’t see because scanners examine what’s installed, not what’s executing. It’s the environmental evidence that turns theoretical projections into actionable intelligence.

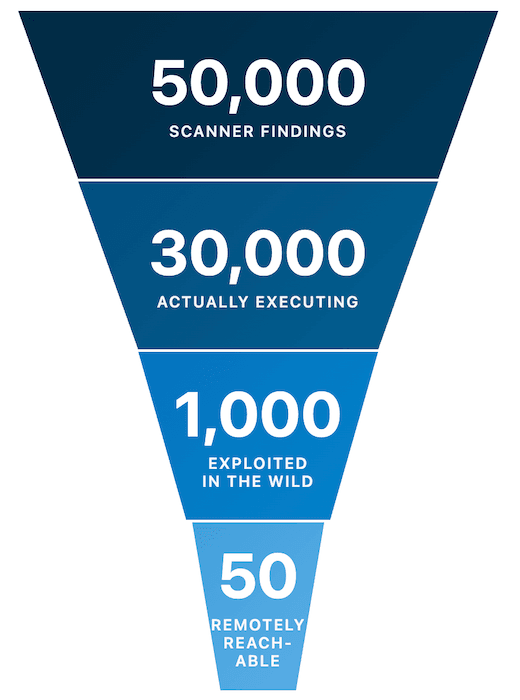

With runtime data, that list of 50,000 vulnerabilities might shrink to 30,000 in software that is actually executing, then to 1,000 that are exploited in the wild, and finally to 50 that are remotely reachable in your environment. Those 50 can then be rank ordered by blast radius: which ones give attackers credentials, persistence, or lateral movement capability?

Example of how runtime context radically reduces the number of vulnerabilities to fix right now

Now your team has a prioritized list of vulnerabilities they can actually work through. Not based on theoretical severity. Not based on what’s being exploited somewhere else. Based on what actually poses risk in your environment, right now.

The Path Forward

Traditional threat and vulnerability management answered “what vulnerabilities exist?” Threat intelligence tools tried to answer “what vulnerabilities matter globally?” The next evolution answers “what vulnerabilities matter here?”

This requires moving from installed-state scanning to runtime-state analysis. It requires knowing what’s running, not just what’s present. It requires context that can only come from observing actual system behavior, not modeling it from the outside.

Your team deserves to know which 200 CVEs to fix, not to be handed 5,000 and told “good luck.”

Stay tuned for the next article in this series: Same CVE, Different Risk, a technical deep-dive into the runtime factors that determine whether a vulnerability is actually exploitable in your environment.*

References

[1] CVE Program. (2025). Metrics. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from cve.org/about/Metrics

[2] Datadog. (2025). State of DevSecOps 2025. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from datadoghq.com/state-of-devsecops

[3] Howland, H. (2023). CVSS: Ubiquitous and Broken. Digital Threats: Research and Practice, 4(1). dl.acm.org/doi/10.1145/3491263

[4] Jeff Aboud, Tenable Blog, April 27, 2020. tenable.com/blog/why-you-need-to-stop-using-cvss-for-vulnerability-prioritization

[5] VulnCheck, “2025 Q1 Trends in Vulnerability Exploitation,” April 24, 2025. vulncheck.com/blog/exploitation-trends-q1-2025

[6] Ponemon Institute and Rezilion, September 2022. rezilion.com/lp/its-about-time-ponemon-survey