Beyond CVE Counts: Detecting Real-World Risks in PDF Editors

PDF editors with zero CVEs can be just as dangerous as those with dozens. Our research shows why organizations need runtime behavioral monitoring, not just CVE tracking.

Published on

Summary/BLUF

PDF editors are one of those categories of software that feel impossible to standardize in your organization, no matter how much you try. You spent months finding the one that meets your needs, and even more time getting the spending approved and onboarding the vendor. Yet you’re still hearing about end users being compromised after downloading software from the first result for “PDF editor” they found on their favorite search engine.

In a perfect world, employees would use only approved software, and TPRM teams would have all the necessary information to make informed decisions. Unfortunately, organizations continue to struggle with policy enforcement, and threat actors continue to take advantage of these gaps.

In this blog post, we outline a more modern approach to software risk assessment as it relates to PDF editors/viewers, highlight the real-world impacts associated with the continued reliance on CVEs as a core pillar for TPRM, and provide an example of how threat actors are taking advantage of the lure of “free PDF editors”.

In our testing, we found that the free applications we tested rarely had published CVEs related to discovered vulnerabilities. Additionally, the paid application we analyzed had a risk grade of “D” based on Spektion runtime detections. If the number of high-severity vulnerabilities and EDR detections is the primary mechanism for determining whether an application poses a risk to your environment, you are setting yourself up for an avoidable visibility gap.

Testing “Free” PDF Editors

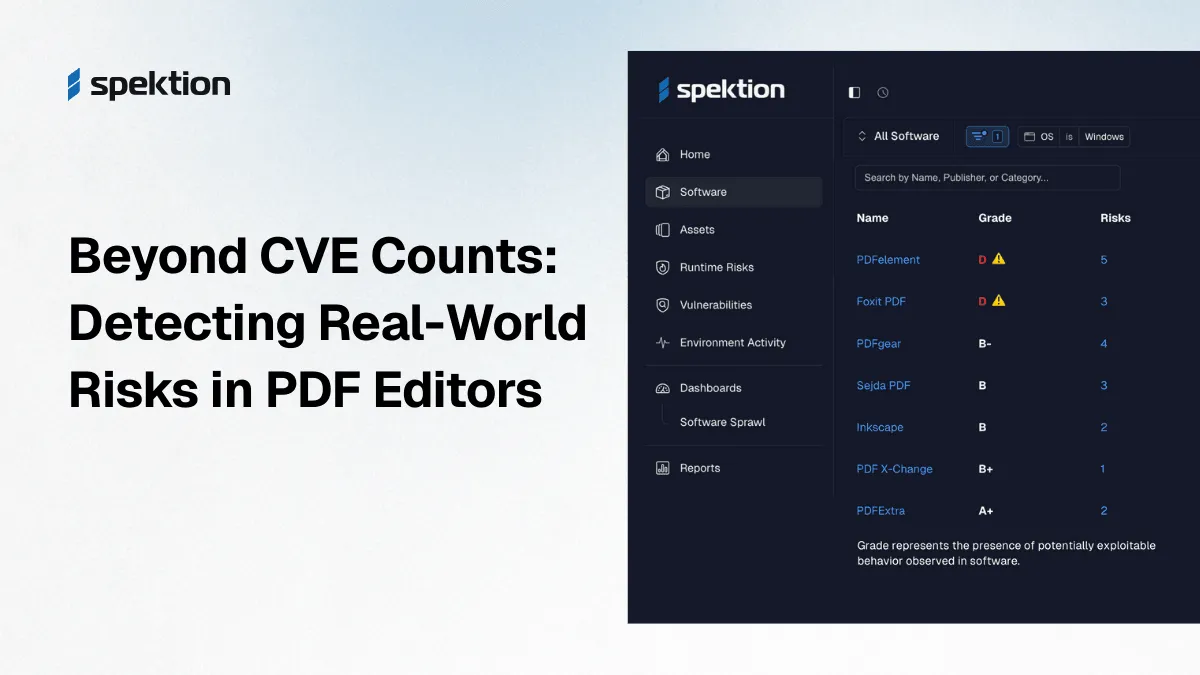

Taking on the role of an end user, we searched for the best free PDF editor using our favorite search engine. Using the results, we installed the most popular applications on a test system running Spektion, a runtime vulnerability management platform that monitors software behavior to detect risks.

Of the six free applications we tested, the riskiest software grade was “D”, having five runtime risks, and two of those risks were running as privileged.

To ensure completeness, we compared a free PDF application with one of the most popular paid options. Both the free (PDFelement) and the paid option (Foxit PDF) received an overall grade of “D” based on their observed runtime risks. The paid application had 26 unique CVEs published in 2025, with 17 of them having a CVSS score of 7.5 or higher. In contrast, and perhaps the more concerning metric for organizations running it in their environments, the free PDFelement application did not have any published CVEs in 2025. Either the free app is much more secure than the paid one, or relying on CVEs as a standard metric for TPRM and internal teams is an outdated fallacy.

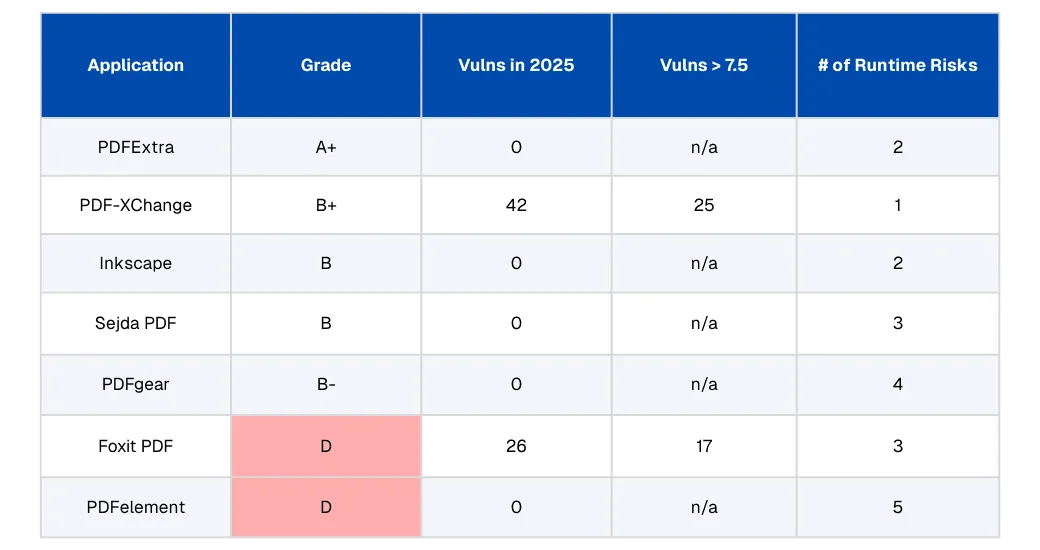

The results of our scenario are outlined below.

Detailed Risk Analysis

Figure 1: Summary of risk grades, vulnerabilities, and runtime risks that Spektion identified across the tested PDF editors

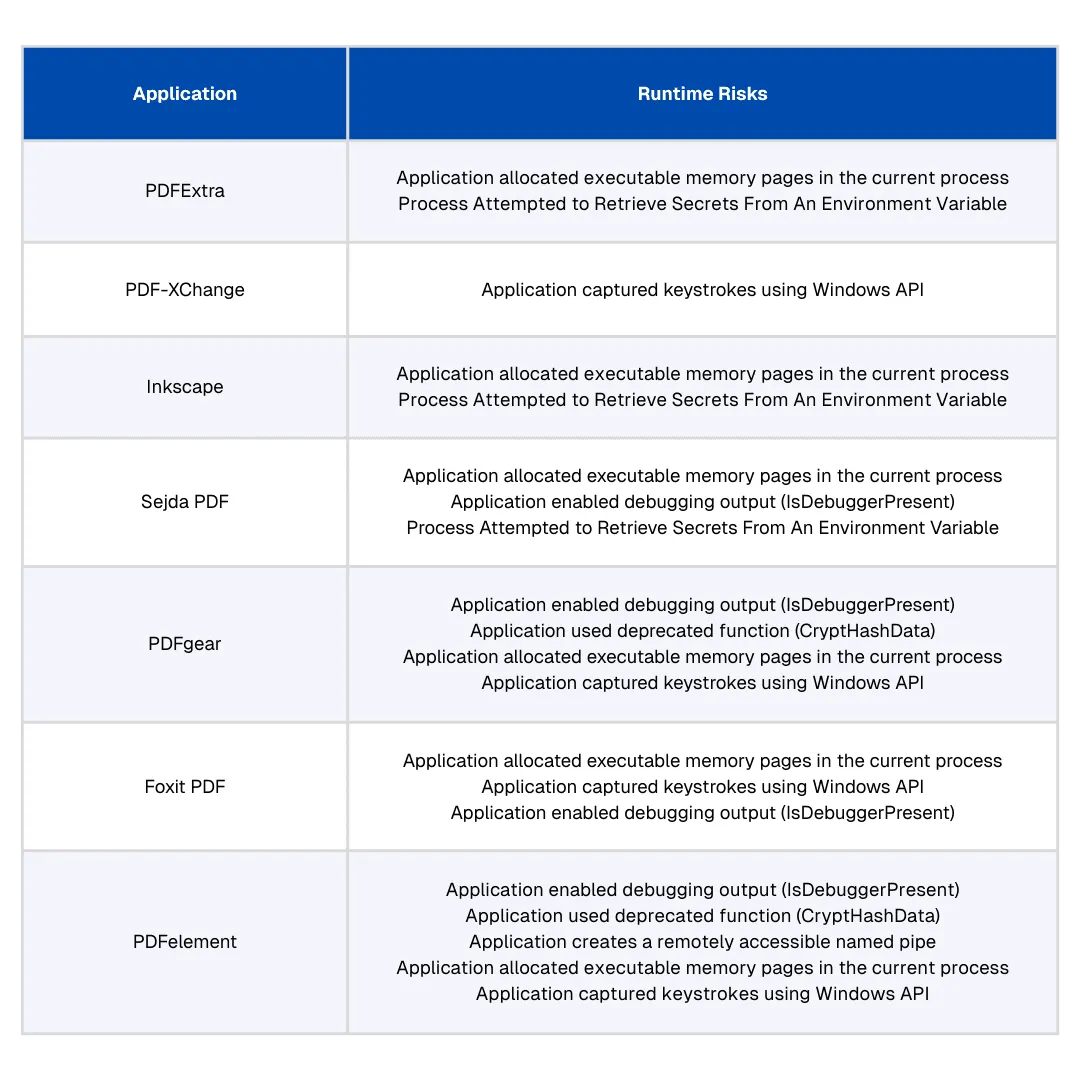

Figure 2: Runtime risks Spektion detected across the tested PDF editors

High Risk Application: PDFelement

While PDFelement had zero published CVEs in 2025, Spektion identified these five runtime risks present in the software, along with their corresponding MITRE ATT&CK techniques and CWE classifications:

Runtime Risks:

- Application enabled debugging output (IsDebuggerPresent) (Privileged)

- Application used deprecated function (CryptHashData)

- Application creates a remotely accessible named pipe

- Application allocated executable memory pages in the current process (Privileged)

- Application captured keystrokes using Windows API

High Risk Application: Foxit PDF Editor

When running on our test system, Spektion identified these vulnerabilities still present in the Foxit PDF Editor software:

Example CVEs:

- CVE-2025-9330 (7.8)

- Uncontrolled Search Path Element Local Privilege Escalation

- CWE-427 Uncontrolled Search Path Element

- CVE-2025-9329 (7.8)

- File Parsing Out-Of-Bounds Read Remote Code Execution

- CWE-125 Out-of-bounds Read

- CVE-2025-9328 (7.8)

- File Parsing Out-Of-Bounds Read Remote Code Execution

- CWE-125 Out-of-bounds Read

- CVE-2025-55308 (8.8)

- Update Service Incorrect Permission Assignment Local Privilege Escalation

- CWE-732 Incorrect Permission Assignment for Critical Resource

Real World Impact: TamperedChef

An article published by TrueSec in August 2025 described research into a campaign where threat actors used Google Ads to promote several fake websites, ultimately directing users to sites offering a free PDF editor.

The software remained inactive for about 56 days and was only being flagged as a potentially unwanted program (PUP). However, an update introduced new malicious capabilities, transforming the software into information-stealing malware. The application in this scenario had no CVEs, installed to the user’s directory, and changed behavior nearly 60 days after initial deployment/installation—a timeline that aligns with typical Google ad campaign lengths, suggesting the threat actor intentionally maximized downloads before weaponizing the software.

This behavior was eventually detected by vendors due to multiple factors, but often that isn’t the case. More often, the only way to find this type of activity is to consistently look for new behaviors, basing your assessments on what an application is doing now versus what it was doing when it was first installed.

In this scenario, Spektion would have detected the new runtime risks associated with the new behaviors and prompted your team to review them. Our approach to runtime risk doesn’t just tell you what’s installed throughout your organization; it also monitors software over time, alerting you to changes in behavior that may warrant additional review or mitigation. This approach allows your organization to make informed decisions about PDF editors and any other software you deploy.

Conclusion

In this blog, we highlighted the importance of approaching risk utilizing runtime risks and behavioral telemetry over CVEs. Free and paid PDF applications will continue to be present in an organization regardless of the policy-defined risk appetite. TPRM and operational teams can make more informed decisions using runtime risks instead of vulnerability or vendor surveys alone.

Regardless of the software category, runtime behavioral data is a more reliable metric for determining the holistic risk of an application versus the outdated method of trusting CVEs and EDR detection ratios. Just because a software suite isn’t suspicious in week 1, it doesn’t mean it won’t be in week 57. The modern threat landscape requires organizations to anticipate where the risks will be so that they can reliably mitigate and/or remediate risk—even when end users download software directly from search results.